Oiseaux de Libye/Birds of Libya

Paul Isenmann, Jens Hering, Stefan Brehme, Mohamed Essghaier, Khaled Etayeb, Essam Bourass and Hicham Azafzaf. 2016. Oiseaux de Libye/Birds of Libya. SEO France. National Museum of Natural History, 55 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France.

Available in UK from NHBS: £46.99 = $62 = €55 (http://www.nhbs.com/title/209267/birds-of-libya-oiseaux-de-libye)

Available in Germany from Media-Natur: €39.90 + international postage (http://media-natur.com/Isenmann-Hering-et-al-Oiseaux-de-Libye-Birds-of-L…)

This is the latest in a series of books about the birds of North Africa whose author or lead author is Paul Isenmann, a notable ornithologist whose reputation has been established for many decades, his driving interest being the changing ecology of the Mediterranean landscape and its effect on birds. The previous titles in the series were Birds of Algeria, Birds of Tunisia and Birds of Mauretania. This volume largely aligns with the IOC taxonomy as of 2015. It is in no way a field guide, but rather a fascinating repository of valuable information.

The layout of Oiseaux de Libye places in the introductory material the French text on the left-hand page and English on the right; in the Annotated Checklist, French is in the left-hand column on each page and English in the right-hand column. This arrangement helped greatly revive and recall my French vocabulary! Data on the birds of Libya has over the decades since the 1960s been sporadic both temporally and geographically due to political restrictions or instability. Nevertheless, by synthesising all forms of data new and old, surprisingly informative conclusions on the changes to bird populations have been reached in this book, whether the birds are residents, migrants or winter visitors. Data sources include, but are not limited to, museum specimens, old books and papers (including several by the current Editor of Sandgrouse, Peter Cowan), records of birders, ringers and researchers who worked for oil companies or in schools in Libya, popular and technical papers on birds, bird biology, bird movements, grey literature, personal records, some very recent studies (especially those involving one of the co-authors, Jens Hering), and perhaps the most invaluable source of all, the records, papers and unpublished notes of the authors, especially valuable being those of the Libyan co-authors. The closely-packed Reference List of 19 pages, in continuous listing, is a remarkable achievement indeed, one that will be heavily consulted.

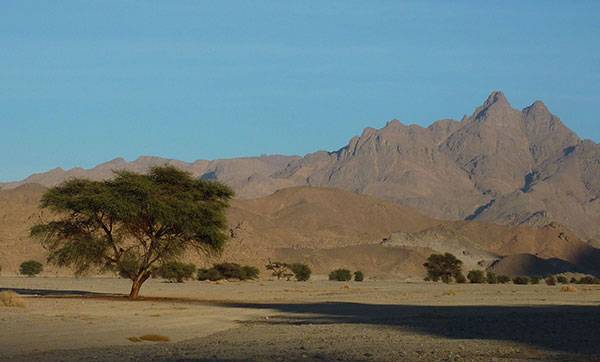

Before the Annotated Checklist that forms the bulk of the book, there are six concise pages on the Geography and Climate of Libya – there are nuances here that probably have escaped many people such as myself despite my good basic knowledge – then comes a short History of Ornithology in Libya, followed by a Biogeographical Analysis of Birds Breeding in Libya. Interspersed throughout this material are colour images of the main Libyan habitats, which instantly help understand why gathering data can be so difficult – the Sand Sea of Ubari is a formidable sight! Inset into some images are excellent bird photos. Examples of both decorate this review (All images copyright Jens Hering). There are also several tables of the various categories of birds of Libya. Appropriately, the Mediterranean and Palearctic-Afrotropical Migration Systems in Libya are summarised before the largely depressing section, Birds and Man in Libya. My only regret about the foregoing is that the single map is but general in character. Should there be a second edition, I suggest that an additional four maps, one per region designated in the book, should contain all the places named in the gazetteer at the end of the book. As it is, the gazetteer would be much more useful had it included latitude and longitude coordinates for each location listed. In the Annotated Checklist, records of selected species are placed on medium-sized maps which give tantalising glimpses of what could be achieved with better and more consistent coverage, yet the synthesis of data from a wide variety of sources has achieved its goal marvellously, a solid baseline for future work in that little-known country.

Rufous-tailed Scrub Robin Cercotrichas galactotes SE Libyan Desert. Photo: Jens Hering

Because Libya lies on and outside the limits of the OSME Region, I am restricting my comments on the Annotated Checklist to those species that either occur also in Egypt and elsewhere in the OSME Region, or that occur closer to the western Egyptian border than other sources had indicated, thus being potential wanderers to the OSME Region. I should emphasise that not only has much invaluable recent data been obtained in parts of Libya, but also an increasingly rich data source is that of radio-tagged migrants, something the authors have pursued assiduously.

The Annotated Checklist contains many nuggets of information. For example:

- It is now near-certain that the North African Red-necked Ostrich Struthio c. camelus is extinct in Libya.

- There are three records of Cape Teal Anas capensis from easternmost Libya, unfortunately from 1961-68.

- Cyrenaic Partridge Alectoris (barbara) barbata, which may be a full species and is known to still breed in NW Egypt, appears to be in rapid decline in NE Libya: it breeds nowhere else and so should be considered as an urgent conservation priority.

- There are no recent records of Little Bustard Tetrax tetrax in eastern Libya, which augurs badly for its winter visitor status in Egypt.

- Whether or not Lesser Sandplover is lumped as Anarhyncus mongolus or not, its occurrence in Libya may be questioned. The smallest subspecies columbinus of Greater Sandplover A. leschenaultii occurs in the eastern Mediterranean and many old records of Lesser Sandplover cannot be safely separated from columbinus; as a consequence, Lesser Sandplover has been removed from the Cyprus Checklist. If it has not already been done by the authors of Oiseaux de Libye, I would submit that Libyan Lesser Sandplover records undergo the same scrutiny.

- In the early 20th century, the now presumed extinct Slender-billed Curlew Numenius tenuirostris “was the commonest curlew wintering in North Africa”.

- Sooty Falcon Falco concolor breeds at al-Jaghbub Oasis, only 60km from Egypt’s Siwa Oasis and 215km from the Mediterranean.

- First Fan-tailed Raven Corvus rhipidurus for Libya was recorded near the SW Egyptian border in 2005.

- Our understanding of Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus evolutionary history and taxonomy is developing at a staggering rate. The authors understandably aligned with the conclusions of a 2015 paper that concluded that the evidence for splitting the Canary Islands and North African populations, C. teneriffae, into 5-7 species was not fully supportable. However, a 2016 paper, published recently largely by the same authors of the 2015 paper, has now found molecular justification at a deeper level for the splits: their research has found three separate colonisation events of the island populations. The Cyrenaica Blue Tit C. cyrenaicae is only 300km from NW Egypt and may turn up after strong westerlies anywhere that has bushes or trees along that region.

- The margaritae subspecies of Dupont’s Lark Chersophilus duponti, resident in NW Egypt is likely rare and declining in NE Libya.

- A new subspecies, ammon, attributed to Eurasian Reed Warbler Acrocephalus scirpaceus has been found breeding in reeds, trees and palms at Siwa Oasis in easternmost Egypt. Given that much recent taxonomic rearrangement of the Reed Warbler complex is inevitable following molecular research into the baeticatus/scirpaceus/avicenniae groups and that as a first step a new species covering Iberia and much of North Africa into Libya, A. ambiguous (Informally named in the OSME Region List as ‘Brehm’s Reed Warbler’), there clearly is much to be clarified. Perhaps the eastern Libyan Oases hold the key?

- The recently discovered (from museum specimens) subspecies cyrenaicae, breeding in N Libya, of Western Orphean Warbler Sylvia hortensis is likely in decline, there being no record in NE Libya since 1923.

- The thinly widespread breeding Western Mourning (‘Maghreb’) Wheatear Oenanthe (lugens) halophila of NW Egypt possibly occurs in NE Libya, but its status is uncertain.

All the above bullet points help build a bigger and clearer picture of what we know about these species. Perhaps more important is that in many cases the book’s information also defines better what we don’t yet know. The book is packed with invaluable data for researchers professional or amateur, but first and foremost it must be acknowledged that the efforts of many Libyans in recent decades underpin the high quality of the end result.

Most encouraging is the Formation of the Libyan Bird Society in 2011. However, the ongoing instability is a tragedy for the people, for and amid the chaos the lesser concern of illegal killing of birds for food has increased considerably.

Mike Blair

02 Sep 2016