Guest blog by Laith Jawad with support from Mudhafar Salim and Salwan Abed

This guest blog is by Laith Jawad, editor of a new book: “Southern Iraq’s Marshes Their Environment and Conservation”, published by Springer, Switzerland in 2021. This multi-authored book contains 40 chapters written by experts in their field. Both basic and applied information is made available, making essential reading for a wide spectrum of users. Mudhafar Salim and Salwan Abed wrote the chapter on birds. The account below is based on some of the chapters.

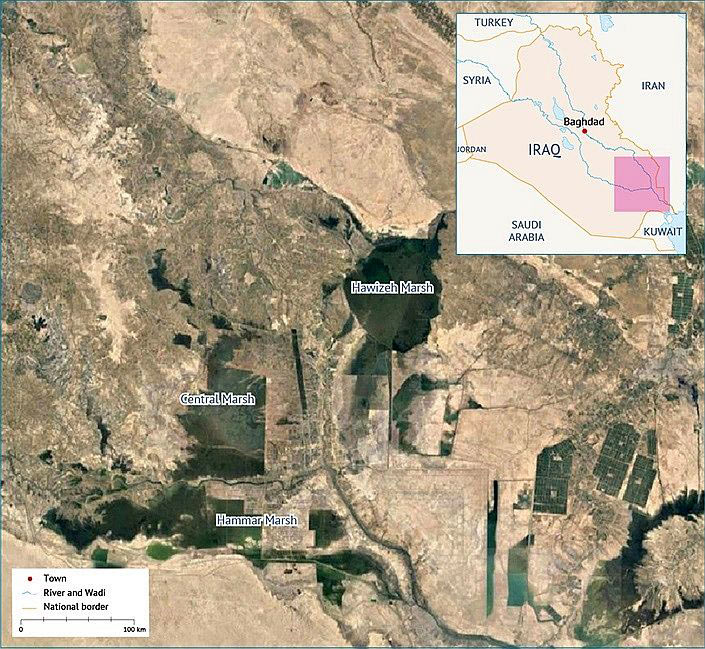

The Near Eastern wetlands are the vast marshes of southern Iraq (alahwār) in the lower Mesopotamian region, an impression shaped tectonically as a consequence of the Arabian plate being subducted beneath the Iranian or Eurasian plate. These are considered famous among the lower lands in the Middle East. These wetlands covered in 1970 an estimated area ranging from 15,000 to 20,000 square kilometres. The eastern margins of the marshlands spread over the boundary into south-western Iran, and they, therefore, create a transboundary ecosystem under shared responsibility. Euphrates River is the prime supplier of marshes with water, with contributions from tributaries of Tigris River. The fundamental region of the marshes is located in the area around the convergence of the Tigris and Euphrates. Therefore, the whole marsh area is divided into three major areas: Al Hammar Marshes; the Central Marshes and Al Hawizeh Marshes. These three marsh zones have been at the centre of the great fluctuations that have been in process over the years. Marsh inhabitants who experienced a mixture of pastoralist, inactive and marsh existence grounded on the periodic growth and collapse of the marsh waters have been recognized including the Maʿdān (Marsh Arabs) of southern Iraq. The majority of the area of the marshes in Iraq is covered with aquatic plants that are dominated by reed (Pharagmites communis) and reedmace (Typha augustata) in the transient seasonal zone. Situated on the routes of the migratory birds, the marshes are chiefly significant for birds. The marshlands set up a main wintering and staging area for waterfowl travelling between breeding grounds. The environment of the marsh area in Iraq has experienced several kinds of influences. Among such impacts was the influence of the changes in the water supply due to building dams in the upper Mesopotamian plain in Turkey and Iran and the ecocide that Saddam Hussein has implemented when he ordered to dry the marshes. The results of drying the marsh areas have impacted the lives of the inhabitants of the marshes in the early 1990s; accordingly, the Marsh Arabs have been compulsory to flee their areas. Besides the engineering workings, their birthplace converted to be one of the chief areas of fighting that overwhelmed southern Iraq in 1991–1993. Owing to the huge loss in the marsh areas, the wildlife and biodiversity have been severely influenced. Such impacts were extended outside the borders of Iraq and showed effects on both the regional and the international levels.

Geological perspectives

Maybe the most famous of the Near Eastern wetlands are the vast marshes of southern Iraq (al-ahwār) in the lower Mesopotamian region, an impression shaped tectonically as a consequence of the Arabian plate being subducted beneath the Iranian or Eurasian plate. Geomorphologic investigations in the area have acknowledged the development and enlargement of the marshes as an advanced trait that augmented over time. Originally, throughout the Last Glacial Maximum (16,000 BCE), the marshes did not exist owing to the very low groundwater, and the Arabian Gulf was rather shallow. At that time, the sea level ascended during the Postglacial (12,000 BCE), carrying the coastline more inland. In the third phase, the aridity of the weather and descent in sea level, inaugurating in the third millennium BCE and enduring into the second millennium, alleviated the deltaic progradation of the coasts and caused the waters of the Gulf and coastline to retreat considerably to their present location, establishing a clean basin that gradually filled in with saline-brackish lagoons and tidal flats (sabkha) over the extended delta land. Ultimately, these were established into small, everlasting freshwater marshes and lakes by the first millennium BCE.

The major divisions of the Iraq Marshes

The marshlands of lower Mesopotamia extend from Samawa on the Euphrates and Kut on the Tigris (150 km south of Baghdad) to Basrah on the Shatt al-Arab. The wetlands create a series of almost interrelated marsh and lake developments that overflow one into another.

Throughout periods of high floods, large areas of the desert are underwater. Thus, some of the previously discrete marsh units combine together, forming larger wetland complexes. In the marsh area, there are wetlands and lakes separated by small islands. These comprise stable and periodic marshes, shallow and deepwater lakes and mudflats that are frequently flooded during periods of elevated water levels. The fundamental region of the marshes is located in the area around the convergence of the Tigris and Euphrates. Therefore, the whole marsh area is divided into three major areas: Al-Hammar Marshes, Central Marshes and Al-Hawizeh Marshes. These three marsh zones have been at the centre of the great fluctuations that have been in process over the years.

Al-Hammar Marshes

The marshes known as Al-Hammar are located south of the Euphrates, traversing from near Al-Nasiriyah in the west to the outskirts of Basrah City on the Shatt al-Arab River in the east and its size ranges between 2899 km2 and 4.500 km2. The water is slightly brackish owing to its location near the Gulf, eutrophic and shallow. It reaches a maximum depth of 1.8 m and about 3 m at a high watermark. The Euphrates River is the main supplier of water to this marsh. A substantial amount of water from the Tigris River, spilling over from the Central Marshes, also sustains the Al-Hammar Marshes. The Al-Hammar marshes support one of the most important waterfowl areas in the Middle East, both in terms of bird numbers and species diversity. The enormous reed beds offer an ideal environment for breeding birds, while the mudflats support many waders.

The Central Marshes

Situated just north of the convergence of the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers, the Central Marshes are at the focal point of the Mesopotamian wetland ecosystem. They obtain water directly from the Tigris River (branches of Shatt al-Muminah and Majar al-Kabir in addition to the Euphrates from its southern side) and extend over 3000 km2 and during flooding can encompass about 4000 km2. Included with these marshes are smaller marshes such as Al Zikri Marsh and Hawr Umm al Binni, which are situated around the middle of the Central Marshes.

Al-Hawizeh Marshes

These marshes are located at the eastern side of the Tigris River and extend across the Iran-Iraq border, the Iranian part being known as Hawr Al Azim. They receive their water supply from branches of Tigris River near Al-Ammarah City known as the Al-Musharah and Al-Kahla. An additional water supply enters these marshes through the Karkheh River in the east. These marshes showed to have a length of about 80 km from north to south and a width of 30 km from east to west and with an approximate area of not less than 3000 km2. These marshes are characterised as having water in the north and middle parts around the year, and the southern part is seasonal. The water of these marshes links Shatt al-Arab River 15 km south of Al-Qurnah via the Al-Swaib River.

The People of the Marshes

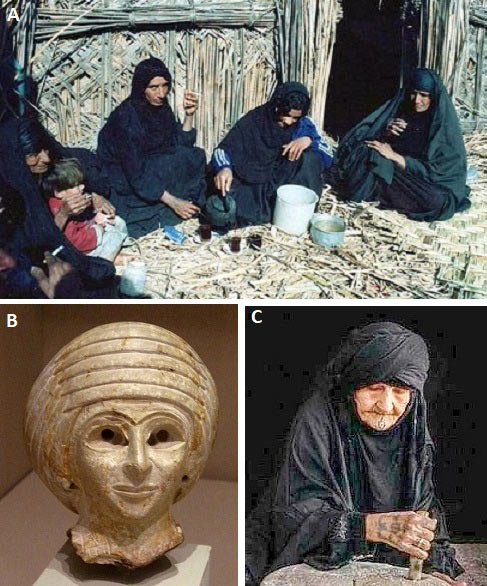

It is thought that the civilization of the wetlands in Iraq can be traced to the time of Gilgamesh who cited this area in his Epic while he was looking for an effective herb to him in perpetuity. The major group in the marshes is the Arabs. Some tribes arrived preceding the Islamic takeover and some through and after it. Based on anthropological evidence it is suggested that there are two main groups that have a clear power in both racial and cultural ways in the marsh areas. These are known as “The Eastern Group” and “The Western Group”. The former includes the Ma’dan, Albu Muhammad and other communities in the Tigris marshes; they had associations with societies across the border in Iran over visiting and marriage. The latter group includes the non-Ma’dan Euphrates Marsh Arabs, and they had relations with the Bedouin societies of the Arabian Peninsula through the same ways as the eastern group had with Iranian societies.

Generally, the people living in the southern marsh areas of Iraq can be known by three names: Ma’dan, Marsh Arabs, and marsh dwellers. The word Ma’dan has various meanings. The Marsh Arabs consider that the word ‘Ma’dan’ is initiated from “Ma’aidi” which represents the enemy, and another view proposes that it stems from “Mou’adat” which is the Arabic word for unfriendliness and dislike. There is a belief that the word “Ma’aidi” came in usage after the British forces had completed their invasion of Iraq and on reaching the marshes were confronted by fierce opposition from the local inhabitants. It is suggested that another version of the word Ma’dan, came from the dwellers who rely on raising water buffalo and selling its products to earn an income. Here, at this point, it is possible to differentiate between the two societies, the Ma’dan and other Arab tribes. In the Ma’dan society, women can work in trading animal products in the markets and they have almost freedom of wandering around outside their living areas, contrary to those of the other Arab tribes that forbid their women from trading outside their home area alone.

On the other hand, Marsh Arabs express the people who dwell in the wetlands. They are under the effects of the nature of their habitats that they living in. Therefore, their cultural, social activities and economics have risen from such an environment. Furthermore, the word ‘Marsh Arabs’ is designated to define groups of people that do not raise buffalo and their women cannot wander around alone as Ma’dan do.

The human societies that live in the marshes are known as Marsh Dwellers. They have their own communal morals, conducts, and ethnicities. This word is used mutually with the term Marsh Arabs, but it has more topographical and ecological implications to show the usual, communal and ethnic influence on the dwellers of wetlands.

The inhabitants of the marshes in Iraq are followers of various religions stemming from ancient time. The majority of people are Muslims followed by Sabians and Jews, but no Christians. Evidence of this ancient belief can be seen in the memorials of each religion. The interesting thing about these diverse religious groups is that they were living in peace and integration for centuries. In the last few decades and due to the political status in Iraq, the number of Sabians and Jews was reduced dramatically.

Habitat Loss

At least 7600 km2 of main wetlands (leaving out the seasonal and temporary flooded regions) disappeared between 1973 and 2000, most of the change happening from 1991 to 1995.

The most impacted are the Central and Al-Hammar Marshes. Of the original 3121 km2 area of the Central Marshes in 1973, only 98 km2 or 3% remained in 2000.

Al-Hammar has diminished to 6% of its original extent. Once more, the remaining area is largely concentrated around the canals and does not constitute a real part of the original wetland system.

Al-Hawizeh has experienced a comparatively less severe decrease in its surface area. However, it has also diminished by 2000 km2, leaving in place only a third of its original size.

The problem of water shortage is likely to hasten as a consequence of the considerable amounts retained by the Karkheh Dam and the future plans to transfer water from its reservoir to Kuwait.

The impacts of the changes in drainage has influenced not only the marshes, but also the north-western part of The Gulf. The reduction in the freshwater discharge from the Shatt al-Arab River and the cessation of the filtering action of the marshes have led to drastic changes in the marine environment around Warbah Island at the Iraq-Kuwait border, and the water quality has degraded significantly with possibly harmful impacts on regional fish populations.

Refugees

The results of drainage impacted the life of the inhabitants of the marshes in the early 1990s. Accordingly, the Marsh Arabs had been made to flee their homes. Besides the engineering workings, their birthplace became one of the main areas of fighting that overwhelmed southern Iraq in 1991–1993. Many marsh villages were surrounded and damaged and their dwellings set on fire. According to reports of Human Rights Watch and the United Nations different chemicals were to the water. For those who remained documentation about their life status showed that a high percentage dispersed to the outskirts of the big cities. The Marsh Arabs who were forced to leave their homeland are entitled to have the designation of “Environmental Refugees”. Such a term was documented in a UNEP commissioned study “as those who had to leave their habitat, temporarily or permanently, because of a potential environmental hazard or disruption in their life-supporting ecosystems.”

Wildlife Decline

Owing to the huge loss of wetlands in the Iraq Marshes, wildlife and biodiversity have been severely affected. Such impacts extended outside the borders of Iraq and showed effects on both regional and international levels. Wildlife specialists agree that the devastation of the wetlands would lead to the global disappearance of the endemic smooth-coated otter subspecies and the bandicoot rat as they were exclusively reliant on this special habitat. It could also lead to the disappearance in the Middle East of the African Darter and the extermination in Iraq of the Sacred Ibis, Pygmy Cormorant and Goliath Heron. The drying of the marshes has almost certainly affected the numbers of migratory and wintering birds.

The above account reflects the contents of the recently published Southern Iraq’s Marshes Their Environment and Conservation. The first section of this book covers the historical perspectives, which focus on the relationship of the present-day Marsh Arabs and their ancestors, the Ancient Mesopotamians, who lived in the south of Iraq for more than 5000 BC. The second section – of five chapters – cover the environmental factors affecting the aquatic ecosystems of the marshes, including chemical, physical and hydrological. The third section gives an account of the geological formation of the marshes.

The major part of the book, some eight chapters, is devoted to the biodiversity of the marshes and the various aquatic organisms they support, ranging from phytoplankton and plants to fish, birds and mammals. A summary of the chapter covering birds, The Ornithological Importance of the Southern Marshes of Iraq (by Mudhafar Salim, Salwan Abed and Richard Porter) appears at the end of this blog.

The book also pays attention to human health in the marshes. One chapter, for example, deals with the consumption of fish by mothers and children in the fishing communities, while another discusses the problem of ingestion of fish bones and the effect of such human health.

Another section of the book covers the environmental challenges in the marshes. Different types of pollution, including chemical and thermal, are discussed as well as ecotourism and the awareness of the marsh community towards it. Whilst the penultimate section, of four chapters, is devoted to the conservation of the marshlands. Building a scheme to protect the biodiversity and the environment, management of the national parks and the unexploited natural wealth of the marsh area are some of the subjects covered.

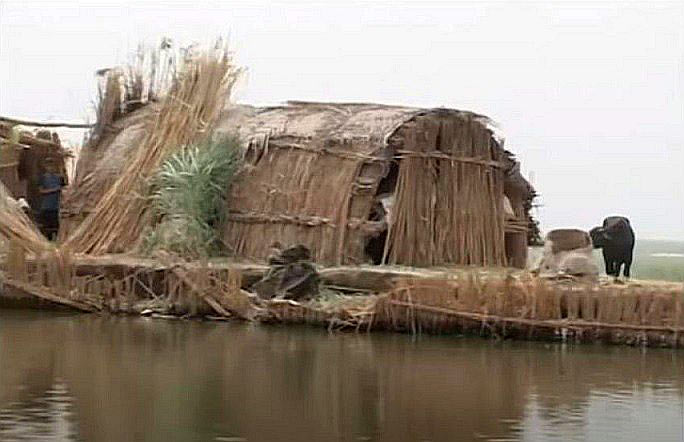

The last part of the book is devoted to the socio-economics of the marshes. It covers many subjects including the creation of new jobs for the Marsh Arabs, the problem of movement of young people in search of a better life outside the area of the marshes as well as discussing the general socio-economy of the marshland community. One chapter describes the daily life of the Marsh Arabs: how they live, what they eat, how daily jobs are split between different family members, how they build their dwellings, what animal they breed, what skills they have. All these aspects are supported by many photographs.

The book serves as an up-to-date comprehensive source of information on the different aspects of the southern marshes of Iraq. Whilst it is aimed at academic scholars, environmentalists, and decision-makers, it is hoped it will be enjoyable for anyone interested in this unique and precious place.

Laith Jawad. School of Environmental and Animal Sciences, Unitec Institute of Technology, 139 Carrington Road, Mt Albert, Auckland 1025, New Zealand

The birds of the Iraq Marshes

The extensive surveys that have recently been undertaken by ornithologists show that despite the drainage during the 1980s and1990s, no species has become extinct as a breeding bird in the marshes of southern Iraq. During these surveys, a total of 264 species of bird have been recorded in the marshes of which 77 have been found to breed – and a further eleven probably breed. Of the breeding species, 54 are resident in the marshes though some also have migrant populations. Furthermore, a total of 197 species are regular winter visitors or passage migrants from Europe and Asia and a further 20 species are rare visitors or vagrants. Some species that were regular winter visitors or passage migrants 50 or more years ago no longer occur.

In terms of conservation priority, 25 species that regularly occur are Red Listed as globally threatened or near-threatened. Of these, the marshes are considered to be of the greatest importance for Marbled Duck, Ferruginous Duck, Common Pochard, Greater Spotted Eagle, Eastern Imperial Eagle, Basra Breed Warbler and probably Black-tailed Godwit. An additional four breeding species have been recently designated as regionally threatened, namely, African Sacred Ibis, Goliath Heron, African Darter and Pygmy Cormorant with a further six breeding species designated as regionally near threatened. Furthermore, the marshes hold globally or regionally important populations of 30 species, two of which, the Basra Reed Warbler and Iraq Babbler, are endemic to Iraq and three have highly restricted ranges in the Middle East: African Darter, Goliath Heron and African Sacred Ibis.

As previously mentioned, the marshes provide important breeding habitat for many wetland birds and, in the case of some species, hold the highest population in the world. In terms of global significance, the Endangered Basra Reed Warbler is the most important with Iraq probably holding over 90% of the world breeding population, with breeding also in the Mesopotamian Marshes in Iran and isolated populations Kuwait and Israel.

We must also highlight the importance of the Ahwar (the marshes) for endemic species and subspecies. The Basra Reed Warbler has previously been mentioned and another is the Iraq Babbler. In addition, the Grey Hypocolius, a Middle East endemic, has a large breeding population in and around the marshes. Four endemic subspecies are also worthy of specific mention: the Black Francolin, Little Grebe, African Darter and Mesopotamian Crow.

Winter Visitors and Passage Migrants

In addition to the breeding species and sub-species, the marshes of southern Iraq are crucial as a stop-over site for migrating and wintering birds. A total of 197 species are regular winter visitors or passage migrants, breeding in Eurasia and dependant on these vast wetlands for resting and refreshing on their long migrations. The Ahwar are crucial for the survival of many species that have to face the long migration over the inhospitable deserts of Arabia and northeast Africa. This is especially so during spring migrations when arriving at a vast wetland complex will, for many species, provide the first large resting and feeding area for probably over 3000 km. In winter the marshes support vast numbers of waterfowl, most notably Marbled Duck with estimates of over 20,000 – some 50% of the global population.

Mudhafar Salim. Natural Heritage Division, Arab Regional Centre for World Heritage (ARC-WH), Manama, Kingdom of Bahrain.

Salwan Abed. College of Science, University of Al-Qadisiyah, P. O. Box 1985, Iraq.

Thank you for this timely publication on the marshes, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Social media platforms can be very effective to amplify some of the issues raised in the book, to reach out to the general public in the middle east – create awareness and start a ‘conversation’.

I was born in Iraq before moving to the UK and remember reading about the marshland as part of my post graduate degree at SOAS, University of London

If you think i can help, let me know.

kind regards