Guest blog by Steffen Oppel

Ten years ago, the Egyptian Vulture population in Eastern Europe was in freefall because too many birds were killed by human activities wherever they went along their migratory journeys. By expanding conservation efforts across three continents, conservationists have now shown that even such globetrotting species can be rescued.

Many migratory species across the world are threatened. Life is inherently risky when the annual routine involves journeys of thousands of kilometres across many political borders, with the risk of getting shot in one country, poisoned in another, and electrocuted in the remaining dozen countries that are crossed on the way to more benign wintering climates.

Conservationists often despair when they are faced with the plight of migratory species. With enormous effort, a species can be protected in either its breeding or wintering areas, but those efforts come to nothing if the carefully protected birds then vanish during migration in other parts of the world.

The Egyptian Vulture, Europe´s smallest and only long-distance migratory vulture, is a typical example of a threatened migratory species: in eastern Europe, the population plummeted from >600 pairs in the 1980s to ~50 pairs in 2018, with many threats along the entire flyway from Europe via the Middle East to Africa contributing to the decline. Since 2010, conservation managers in Bulgaria and Greece tried to save the Balkan breeding population, but until 2018, the population continued to decrease.

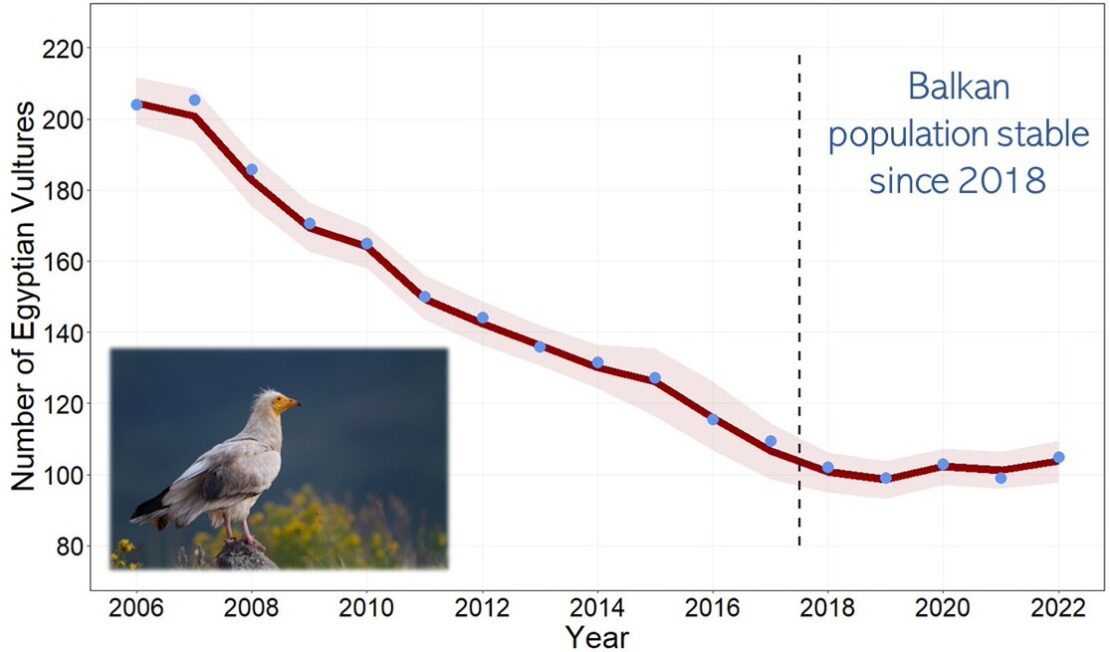

An ambitious project funded by the European Union then expanded the work along the flyway, involving 22 partners from 14 countries across three continents. A new paper in the journal Animal Conservation published on 21st November 2023 now shows that the population in the Balkans has stabilised since the conservation work was expanded from Europe to the Middle East and Africa.

Led by conservationists from the Bulgarian Society for the Protection of Birds/BirdLife Bulgaria, this project spearheaded important monitoring and conservation work in the Middle East, for example the support for two migration monitoring stations in Sarimazi (Turkey) and in Galala (Egypt), support for Lebanon’s fearless anti-poaching units working with local communities to reduce the indiscriminate killing of migratory birds and giving several Egyptian Vulture’s a second chance, and support for conservation in Iraq and Jordan. Through collaboration with electricity companies many dangerous powerlines were refurbished in Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Egypt. The project team also organized an international conference focused on the Egyptian Vulture, with attendants from three different continents and status updates from several countries in the Middle East.

After 6 years of hard work the project team had reduced the risk of poisoning, electrocution, and direct persecution in 14 countries along the flyway and initiated a species reinforcement programme in the Balkans by releasing captive-bred individuals donated by the European Endangered Species Programme (EEP) of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). As a consequence of this work the annual mortality rate of Egyptian Vultures decreased by 2% for adult birds and by 9% for juveniles. Although these changes seem minuscule, they had an encouraging effect: since 2018 the Egyptian Vulture population on the Balkans has not decreased further but remained stable around 50 breeding pairs.

Arresting the decline of a threatened migratory bird species is a major success, but the team cannot rest on its laurels just yet. Much of the success requires ongoing work to remove poison from the countryside, to reduce the illegal killing of birds, and to manage the ever-expanding network of poorly located and designed powerlines that function as death traps for birds. Persistent efforts to reduce these threats are necessary along the entire flyway to facilitate the recovery of the population, and funding is sorely needed to sustain these efforts. However, for once there is a glimmer of hope that with a large team of dedicated people working at truly intercontinental scales, even species that migrate thousands of kilometers can potentially be rescued – a feat that seemed impossible only a few years ago.

Steffen Oppel is a conservation scientist who worked for the RSPB and was responsible for designing the data collection under the Egyptian Vulture New LIFE project. He provided scientific support for BirdLife partners along the flyway, and assisted with managing and analysing data, and disseminating results from the project. Steffen recently moved to the Swiss Ornithological Institute where he now studies the dispersal and survival of Red Kites, Golden Eagles and Little Owls, but he is broadly interested in various conservation issues threatening raptors and seabirds.