Guest blog by Robert J. Burnside

I have been working in the Kyzylkum desert, in Uzbekistan, since 2013 on the ecology and conservation of the Asian Houbara with the University of East Anglia, BirdLife International and the Emirates Bird Breeding Centre for Conservation (www.sustainablehouaramanagement.org). During these years one other bird has really caught my imagination as I was always alerted to its presence by the easily identifiable ki-ki-ki alarm call of the Turkestan Ground-jay Podoces panderi (aka Pander’s Ground-jay, Saxaul Ground-jay, [Photo 1, Video 1]). This is often followed by a vain attempt to get a photograph of this handsome bird as it entices you towards it with its characteristic terrestrial running and hopping while always staying just far enough away to ruin the photograph! However, rather than the bird aspiring to foil budding photographers, this behaviour is actually a clever defence strategy used to draw you away from their nest.

VIDEO 1: Turkestan Ground-jay returning to its nest.

The Turkestan Ground-jay is full of character and unmistakable with its black patch on the breast contrasting against its white/grey plumage. It only occurs in the Kyzylkum and Karakum deserts (within Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan) and is actually the only endemic bird listed in the Turkestan region. It is quite iconic and known by most people that I have met across Uzbekistan while also being top of the list of birds to see for international visitors. Given its near celebrity status, I was surprised when I found that this species had not been subject to any quantitative assessments since prior to the 1980s by Soviet scientists. IUCN assessments have rated it Least Concern since the 1990s based on certain assumptions in the absence of any actual recent field data, so the houbara project provided a good opportunity to piggyback some new work on the species, especially in the face of the rapid and ongoing development causing threats to many natural habitats in central Asia. So I teamed up with my Uzbek friends, collaborators and ornithologists Anna Ten and Valentin Soldatov to develop a project investigating the breeding biology of the ground-jay in the Bukhara province of Uzbekistan. In the autumn of 2018 we successfully applied for an OSME Conservation Research Grant aimed at improving knowledge of the species in the region.

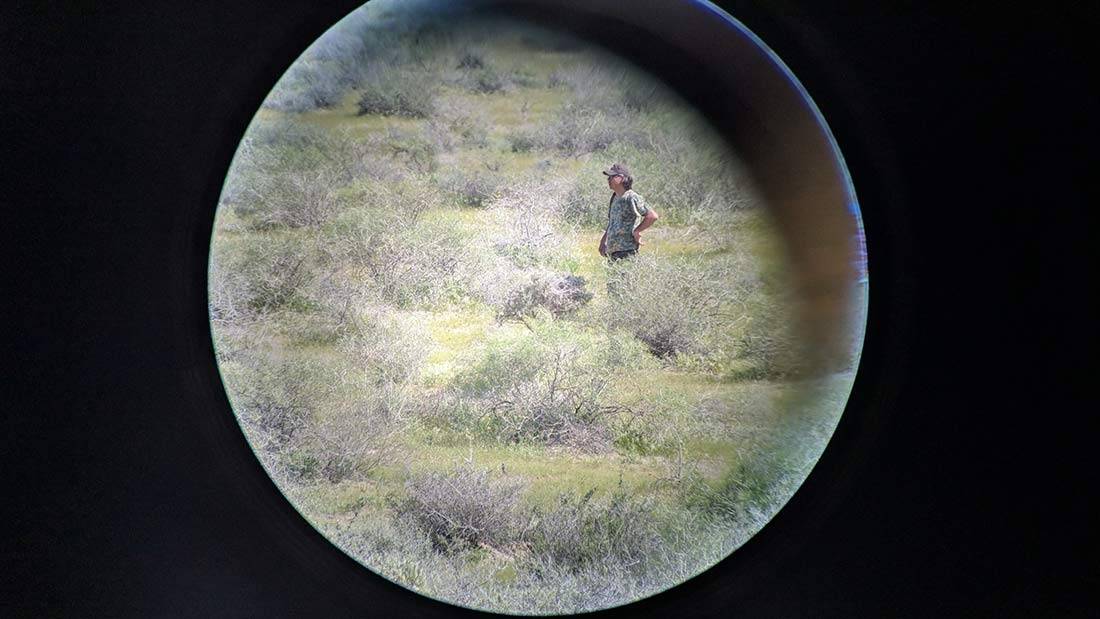

While in the past I had opportunistically come across ground-jay nests, I was uncertain if this could be done on a scale to quantify breeding success. So it was with a bit of trepidation that we set out together in April 2019 (Photo 2) on the first day of fieldwork to see if we could establish a reliable method to find the nests. To my relief, it was not as difficult as finding houbara nests! In fact, we found that ground-jay behaviour can easily alert you to a nest in the area, and on the first day we found two nests. Two methods worked: when a vantage point was available it was possible to use a telescope to spot birds foraging and returning to their nest if they had one, after which you could guide your colleague in over a walkie-talkie (Photo 3). Alternatively, while driving along existing tracks, the birds could be spotted or would flush and perform alarm calls which alerted you to the presence of a nest and the area was then searched by foot for the nesting structure.

Once you get your eye in, the nests are quite easy to recognise as they are often in the middle to a dense shrub, constructed of dried twigs with a loose roof structure and an entrance and exit hole (Photo 4). The nests were often lined with camel hair (Photo 5). The incubation period for eggs is 17 days, the fledging period a further 17 days. This is quite a long period of vulnerability in a desert with many generalist predators.

Every nest found was revisited each week, and some nests also had cameras installed to allow us to identify outcomes and also to understand the nest predators. The team found 37 active nests although in total we found 178 nest structures, showing many were remnant from previous years. The alternative name Saxaul Ground-jay is well earned as we found 42% of the nests were in saxaul shrubs (Haloxylon persicum, a bushy evergreen shrub that can grow several metres if left undisturbed [Photo 6]) even though the species only occurs at a frequency of 1% in the study area, which shows how favoured it is for nesting. Two other shrubs of similar size and bushy structure were also used (Calligonum spp, and Salsola arbuscula [Photo 4]), thus only three shrub species are actually used to nest out of the 19 available, highlighting their importance to ground-jay breeding habitat.

The nest cameras showed that ground-jay nests were prone to predation by a wide variety of predators, including wild cat, hedgehog, diadem snake, red fox, humans and desert monitor lizards. None of these, with the exception of people, we would class as irregular or a threat beyond the natural ecology of the desert.

Video 2: Turkestan Ground-jay nest camera footage showing predations and fledging events.

We did also see nests successfully fledge (see Video 2, Photo 7), which involves an intrepid leap from the nest by the chicks. Overall, we estimated that the probability of a nest reaching fledging was 18.9 % with the main cause of failure being predation. This is similar to the rate found for Pleske’s Ground-jay in Iran which is also prone to a wide but different set of predators. It must be noted that we started our nest monitoring in April, probably about a month after the earliest nests started. Monitor lizards, which are the main nest predator, are inactive during the cooler months of March, so it is probable that earlier nests could do better.

The outcome of this field research highlights just how dependent Turkestan Ground-jays are on a small number of spp. of shrubs (saxaul spp., Calligonum spp. and Salsola arbuscula) for nesting habitat. These shrubs are all exploited by people for the collection of fuelwood, leading to considerable habitat degradation. Sadly, this is the same risk listed in the 1980s so not a lot has changed in that regard. It will be particularly important to maintain habitats that contain these shrub species but also the heterogenous vegetation structure found in Bukhara as this seems to be ideal for ground-jays. The study area in Bukhara must be particularly important for the Turkestan Ground-jay in Uzbekistan as they occur there in much greater numbers than I have seen elsewhere in the country’s other desert regions.

In all, this is a first step into investigating the ecology of the interesting species that we know very little about. While we know the approximate extent of the Turkestan Ground-jay distribution, we still do not know how densities vary across the range, what the population size or trends may be, or the long-term viability of the species. We estimated that only 5.6% of the Turkestan Ground-jay range is currently within existing protected, which is clearly very low. Hopefully, future work will allow us to continue to shed light on the status of this species and how we can best proceed in future to protect it.

We published this research in the Journal of Ornithology and the article is open access and downloaded from here:

Burnside, R. J., Brighten, A. L., Collar, N. J., Soldatov, V., Koshkin, M., Dolman, P. M. & Ten, A. (2020) Breeding productivity, nest-site selection and conservation needs of the endemic Turkestan Ground-jay Podoces panderi. Journal of Ornithology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-020-01790-9

I would like to acknowledge Alex Brighten for her help in the field and during manuscript preparation; to Dr Maxim Koshkin for his input through his dataset on vegetation of the Bukhara region; to Prof. Nigel Collar (BirdLife International) and Prof. Paul Dolman (UEA) for their input into the manuscript; and to the Emirates Bird Breeding Centre for Conservation (EBBCC) in Uzbekistan who kindly supported several aspects of the fieldwork logistics, and without who’s support the work would not have been possible.

Dr Robert John Burnside (goes by John) is a research fellow at the University of East Anglia, UK. He is responsible for coordinating the research programme on the sustainable management of Asian Houbara. He has a background in reintroduction biology and conservation science. As well as Houbara in Uzbekistan, he’s interested in sand cats and ground-jays.